Are the open-plan office, co-working, and hotdesking all dead? Is remote working the new normal? Will our commercial real estate ever be the same again? These are the questions swirling around the buildings industry as we look ahead to the mysterious post-COVID landscape.

“We are, at this moment, probably prone to overthinking a pandemic’s influence [on the built environment],” says Ian Klaus, a senior fellow at the Chicago Council on Urban Affairs. “But pandemics really do prompt profound behavior change.”

It wouldn’t be the first time that disease reshaped our built environment. Improvements in potable water distribution, wastewater extraction, air ventilation, insulation, entry-procedures, and all manner of standard building materials, have all come about in reaction to health and safety issues. The bubonic plague sparked building improvements that reduced contact between rodents and humans, cholera improved the separation of potable and wastewater, each major outbreak serving as a growing motivator to reshape buildings for the good of their occupants.

“Tuberculosis became a driver of the modernist architecture movement, inspiring architects like Le Corbusier—whose avoidance of formal frivolities was a sort of architectural hygiene—to bring light and air into their designs,” says Elizabeth Stinson in an article for the architectural digest. “Eventually, this sanitarium style would influence the trajectory of many affordable housing projects across the United States.”

COVID-19 is the third and strongest of the recent zoonotic coronaviruses, after SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, and the only one to reach pandemic status, so far. Whether COVID-19 is seen as the third-strike and sparks major reform, or is brushed off until next time and changes little, we can still speculate on what could be done to better protect occupants from viruses and how buildings could adapt to a new public health landscape.

“How we think about the workplace will be the biggest change,” says Darren Comber, chief executive of architectural design firm Scott Brownrigg. “We’ve seen a huge boom in co-working spaces. But, after this, are companies really going to want to put their entire team in one place, where they’re closely mingling with other businesses?”

Many more companies will be asking whether they want all their employees in one place or a co-working space. In terms of virus-safety, remote work models with enhanced video conferencing offer the best results and also create huge cost-saving opportunities — but that money is coming straight out of commercial real estate. Opponents to the remote working model will highlight the benefits of in-person collaboration and in-house cybersecurity, but workers are getting comfortable at home and the pandemic is far from over. Commercial real estate may be in trouble unless it can adapt.

“I think we’ll see wider corridors and doorways, more partitions between departments, and a lot more staircases. Everything has been about breaking down barriers between teams, but I don’t think spaces will flow into each other so much anymore,” Arjun Kaicker, analytics and insights lead at Zaha Hadid Architects, told The Guardian. “Office desks have shrunk over the years, from 1.8m to 1.6m to now 1.4m and less, but I think we’ll see a reversal of that, as people won’t want to sit so close together.”

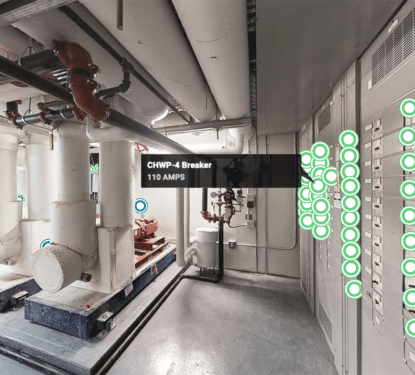

“High-rise buildings would become more expensive to build and be less efficient, which may reduce the economic attractiveness to developers of building tall – and super tall – towers both for offices and residential,” he continues. Kaicker and his team are already putting some of these concepts into action, developing “contactless pathways” for the Bee’ah waste management company headquarters in Sharjah, UAE, for example.

The coronavirus pandemic threatens significant consolidation in the commercial real estate sector, with at least some impact seemingly unavoidable. The real estate sector will fight back with innovative design and technology, but the virus, might still force stronger public health policies, such as extended lockdowns. Without the virus-control measures that buildings promise, the chance of spikes in the virus and stronger policy grows, forcing real estate to adapt or close their doors.

Whichever way the sector looks there is disruption and change. It is hard to imagine, for example, that the real estate industry can ever look at Density in the same way again.

“Density is still a very fraught subject in the US. The pandemic is already giving ammunition to people who are naturally skeptical of density and want to promote the car-centric suburbs. They’re making the same arguments that were made over 100 years ago,” says Sara Jensen Carr, an architecture professor at Northeastern University. “People tend to put the blame on personal choice, but the built environment shapes those choices.”

The centuries-long battle between commercial real estate usage and public health will continue until buildings adapt, just as they have in the past. Nothing will happen overnight, the panic will rise and subside, but it seems increasingly likely that changes will have to happen eventually. Waves of the pandemic will slowly chip away at our entrenched habits; accelerating our evolution to a tech-enabled society, pushing us away from urban living all together, or inspiring a health-focused revolution in the way we use and operate our commercial real estate.