The pyramids of Giza have been standing intact for over 4000-years and are not even the oldest pyramids in Egypt.The Pantheon in Rome has been in continuous use for over 2000-years, Istanbul’s intricate Santa Sophia appears pristine despite is 1483-year age, while the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, Palestine, has housed worshipers for the last 1455-years. We have known how to construct and maintain buildings to last for thousands of years, yet the average life of a modern building is just 60-years and many are now calling that unsustainable.

This trend is not just revealed in comparisons with ancient structures that receive the status and funding for protection and restoration. According to a recent colloquium by the Getty Center, the average life span of relatively modern conventional buildings, built from masonry and wood, is about 120 years, double that of modernist buildings made of reinforced concrete and glass. It didn’t take long to realize that porous, fragile concrete was a poor substitute for stone and brick as external cladding, while the shift to the glass curtain wall only highlighted the gasket, sealant, coating issues of glass that brought about the current 60-year lifecycle of buildings.

"Sixty years! You might say that architects today are delivering half the product that they used to,” says architect and esteemed author Witold Rybczynski. “For a long time, a building’s durability was taken for granted. It might be clad in marble, brick, or stucco, but with adequate maintenance (cleaning, re-pointing, painting, and plastering), it could be expected to last. This was because construction consisted of heavy masonry walls, whether you were building a villa, a palazzo, or a basilica.”

This is not a story of building materials, however, it is one of development. Our desire for bigger and better, safer and more fashionable, in order to increase the value of our finite land resources, especially in crowded cities, has encouraged this shorter building lifecycle. There is more money to be made from creating a building, demolishing it at 60-years-old, and rebuilding with modern methods and styles than constructing buildings to last hundreds of years. The property industry is now being placed under significant pressure to re-think their practices in this age of sustainability.

One example is the push for the buildings sector to adopt a traditional accounting concept — embodied energy — to represent the true environmental costs of these shortened building lifecycles. In accounting, embodied energy aims to find the sum total of the energy necessary for an entire product lifecycle, and for the buildings that includes raw material extraction, transport, manufacture, assembly, installation, deconstruction as well as secondary resources. Meaning, the building that stands ready for demolition carries that embodied energy and the process of demolition largely wastes that energy — unnecessarily in the eyes of sustainability.

“You follow the brick all the way back to the quarry and you figure out what’s going to happen to it in 100 years or 2,000 years,” architectural historian Kiel Moe explained in a 2018 interview with the Yale University journal Paprika. “It’s understanding more of what materials can do and rethinking the thermodynamics. Materials are just a subset of energetics,” a scientific field, has long utilized the concept of embodied energy.

Buildings account for 40% of global energy consumption and 39% of CO2 emissions but also approximately one-third of global fuel consumption. While automation and smart technology are tackling the operational energy efficiency of buildings and construction, much more attention must be paid to the entire lifecycle of buildings and, in particular, their premature demolition. As sustainability rises in the social agenda, we must reverse the trend of declining life expectancy of buildings by designing longer-lasting structures and making better use of the buildings we already have.

“Recent innovations in lower-embodied energy materials—from using fly ash as a cement substitute to building big in timber, a renewable and carbon-sequestering material — offer new approaches to new construction,” says Thomas De Monchaux, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Architecture at Columbia, in an article for Metropolis. “But also, we might stop demolishing quite so much of the built environment that we already have. Average life spans of buildings in the developed world are declining, to around 70 years in America and as few as 30 years in Japan. This is not progress,” he continued.

In 2016, Swedish furniture giant IKEA began building a landmark new store in Greenwich, London, heralding it as “the world’s most sustainable IKEA store” due to its 100,000 square feet of solar panels and rainwater harvesting from its planted roof. However, little attention was paid to the demolition of the 15-year-old supermarket necessary for the construction of IKEA’s “most sustainable store.” That supermarket, built by renowned British architects Chetwoods, was considered state-of-the-art in terms of sustainability when it was built in 1999.

In line with current trends, we may see that IKEA store demolished and something else constructed in its place within 10-years, all in the name of sustainability — when, in fact, IKEA and the next occupiers could have utilized the same supermarket built in 1999 to maximize sustainability. IKEA’s decision to demolish instead of using the same structure was based on the higher value of having a custom-built, cost-effective, modern-looking store with adequate operational sustainability features to satisfy their customers’ need for greener retail decisions, not on true sustainability.

While we have singled out this IKEA project, they are just one example in an ocean of firms that follow this property development approach, claiming sustainability while neglecting the embodied energy of what they are replacing and how long their building is expected to last. We can build more sustainably and we can make better use of existing building stock to enable greater sustainability in the property sector. Recently, we have even seen signs that the tide is turning, with new design, construction, and re-purposing methods being adopted by some major players.

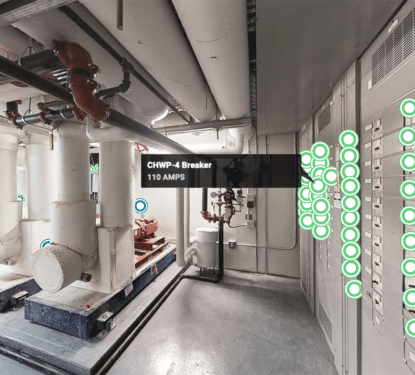

Google’s sister company, Sidewalk Labs, has proposed timber skyscrapers for its now well-known Toronto Quayside development plan. Google itself has chosen to keep using their 27-year-old facility in Mountain View, California, which they inherited from Silicon Graphics in 2003 rather than demolish and rebuild — albeit while expanding the rest of their campus with numerous new buildings. By retrofitting the latest smart and energy-efficiency technologies their older building has been brought up to modern energy-efficiency and workplace-functionality standards with no need for a rebuild.

In the name of sustainability, we need to build less and use what we already have much more, even if those buildings can’t achieve the same levels of operational energy-efficiency as their greenfield counterparts. It is not the fault of corporations and property development firms seeking to increase shareholder value but an issue for the entire sector to take into account. Building certification agencies like LEED and BREEAM, for example, could serve sustainability better by factoring-in embodied energy rather than just heaping praise on the newest, smartest, greenest building regardless of what it replaced.

“Maybe under the influence of thrifty production designers of under-budgeted science fiction movies from the consumerist 1980s, we associate the creative reuse of old stuff with some kind of apocalyptic dystopia. With a poverty of means, not of the imagination. With the aftermath of the current climate catastrophe, not with its immediate mitigation—or even, now at the eleventh hour, with the prevention of its worst consequences,” writes De Monchaux. “But maybe architecture can learn from information architecture, from the practices of all those Google engineers at their very best, to see all of the built environment as hackable, as fungible, as adaptable, as a code with an open-source.”

Follow to get the Latest News & Analysis about Smart Buildings in your Inbox!