Every forward thinking city in the world seems to want to be a “smart city”. An urban utopia where everything is connected, works as efficiently as possible and provides a higher quality of life for its citizens. Around the world, smart cities are emerging by actively experimenting with new information and communication technologies. The idea being that those cities that successfully leverage smart technology will ultimately be the most liveable, sustainable and competitive.

Major world cities like London, San Francisco, Seoul, and Rio de Janeiro, are striving to connect every streetlight, parking space, building and vehicle to a central grid, and accessible by a single municipal control panel and state-of-the-art control centre.

This effort, for all its vision and utopian ideals, has not quite taken shape as quickly and easily as many had thought, bringing up the question – how realistic is the current path to achieving a truly smart city?

All cities, even small cities, are incredibly complex, ever-changing, growing and developing, “living entities”. No two look the same, act the same, or need exactly the same services to meet their unique, dynamic and transitional needs. Each city has a different budget, different demographics, and different levels of citizen engagement. For these reasons, central government led initiatives which apply a “smart city model” to ALL their cities may be destined for failure.

Instead, and according to a growing number of experts, smart cities should start small and, like a city, “smartness” should grow organically and in direct response to the residents needs. A recent report by Dell and HIS ranked US cities by their “future readiness”, and found that each city achieved its rank with a different balance of strengths.

The rankings revealed no definitive formula for achieving future readiness, though education figured prominently. The top four cities (San Jose, San Francisco, Washington D.C. and Boston) were also the top four of cities with the highest percentages of undergraduate and graduate school degrees. The results highlight the importance of a city’s ability to attract people who are engaged in and open to lifelong learning that drives innovation.

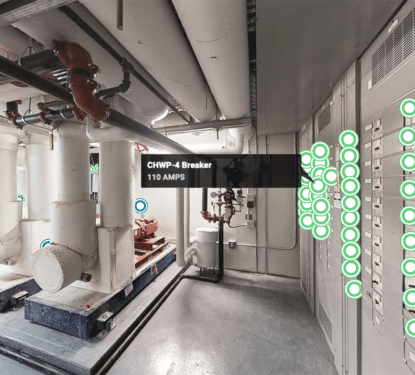

There is a growing feeling, in contrast to the centrally driven system, that cities should start with a small number of buildings or streets, and leverage existing and planned infrastructure upgrades with smart technology choices. These smaller projects should serve as anchor points throughout a city, establishing its foundation as a smart city. Over time, interconnecting smart projects will provide even greater benefits as optimisations between the points can be determined. In summary, they should invest and deploy incrementally.

Where is the logic in rushing to get sensors in all manner of “things” and producing huge amounts of Big Data, if you don’t have the capacity to analyse that data? Take a quick browse of major recruitment sites in the US and Europe, and the number of Data Scientist jobs are staggering. Universities in the same regions are increasing the number of courses in data related subjects. The future capacity to analyse data is growing strongly and steadily, it makes sense to increase data creation at a similar rate.

[contact-form-7 id="3204" title="memoori-newsletter"]

Security and privacy are often named as the biggest obstacles for smart technology deployment. Several recent high-profile breaches have underlined the need to take a measured approach to developing encryption and security protocols. These issues will eventually and inevitably be solved, but a more calculated, measured approach to communication and data security would make the path to a smart urban future a lot smoother.

The top-down smart city development model is rife with limitations. Imagine if the Internet or Smartphones offered only sites and applications by the government or device manufacturer. In that scenario the scale and impact of those fundamental elements of modern society would be a fraction of what they are today. The smart city need not be any different.

A platform from which the public inspires new smart city applications would create an organic system that caters for the need of a city’s residents. The benefits of drawing on the diverse and collective creativity of our tech-savvy society are vast, diverse and proven, albeit a little messy, like society itself. As Memoori explored in a recent article: The Evolution of the Smart City: Top-down to Bottom-up.

A 2014 UN report estimates that by the year 2050, continuing population growth and urbanisation will increase the world’s urban populations by 2.5 billion people. Metropolitan areas are expected to grow by 404 million people in India, 292 million in China, and 212 million in Nigeria. The US is expected to add more than 50 million people to its cities during that time period. The smart cities sector may need to slow down, take a step back, and plan smart city development properly and at a pace that suits society.