Considering that they were first mentioned in the 1980s, it sometimes feels like smart buildings have been around for a while. With every device connected it may appear that the technology is now established, that all that is left is for costs to come down so adoption can pick up and that we are on the verge of that smart urban future we’ve heard so much about. The reality, however, is that we are still very early in our smart building development.

“There is a lack of definition on what a smart building is,” says Reinhold Wieland, business development manager at smart building consultancy firm Connecting Buildings. “I would say “smart” is a combination of smart infrastructure and building automation, real time data, seamless integration, and the real “smart” comes with workflow engines when the building integrates with people in an intelligent way.”

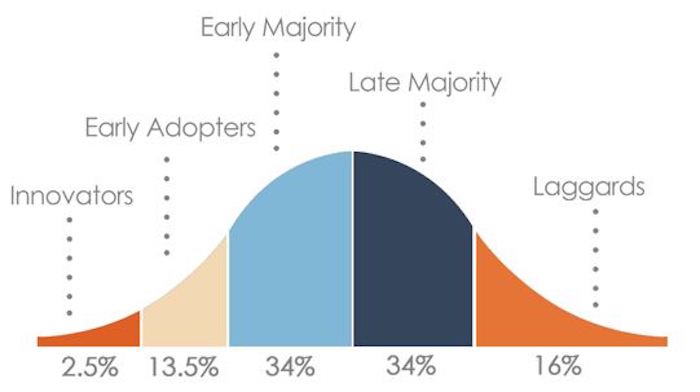

“Based on the Rogers Innovation Uptake Bell Curve, I feel the industry’s maturity is somewhere below the first 10%, but every app or specific technology has its own curve,” Wieland continued in an interview with AllWork. “Perhaps it would be better to grade it on a scale of 1 to 10 or with a star rating. I would say the average of buildings would be on a rating of 3, but many would rank much lower.”

One of the key goals of smart commercial buildings is facilitating the rise of the flexible workplaces being demanded by the tech-savvy, remote and co-working friendly, millennial generation, which now make up more than 50% of the workforce. This new workforce landscape is forcing companies to update their policies towards employees and transform their physical workplaces into smarter, more flexible spaces.

“Younger workers are cutting the cords that tied employees to their desks, through flexible and remote working options,” states our report: The Future Workplace: Office Design in the IoT Era. “Smart design and greater connectivity will be required to ensure spaces and enterprises are equipped for hot desking and remote working, as well as mobile and wearable technology,” the report continues highlighting a variety of emerging trends like co-working and the Workplace-as-a-Service.

This demand from tenants will have “a domino effect on how landlords approach space management, unleashing a healthy competition as they try to attract the mobile tenant market,” says Wieland. Keen to charge premium fees for their space, landlords will be keen to adopt smart technology in order to offer the range of new services that will attract the leading firms, who in turn are trying to recruit the brightest young talent that will demand such modern, flexible workplaces.

“Perhaps, there will be a transparent and open smart building enabled rating for all buildings, which would then attract tenants,” says Wieland. “Smart buildings are more energy efficient, cost less to operate, provide a safer and healthier and happier environment for all the occupants and visitors. All this will speed up the conversion of existing buildings into smart spaces and smart buildings in the flexible workspace arena.”

This is easier said than done, however, there are a number of specific challenges that the sector must overcome in order to encourage widespread adoption. We are not starting fresh. The vast majority of building stock is old and dumb, making those buildings smart is more important than being able to create incredible new buildings. Building systems aren’t being ripped out and replaced with smart versions either, we must work with the services available and gradually encourage their evolution and integration.

“Firstly, building services are not designed to be integrated,” says Wieland. “This has slowly changed for building automation, for example, by introducing common protocols like BACnet, but most other building services are still operating as silos. This is because of inherent security fears and, furthermore, contractors want to protect future maintenance revenues by using legacy systems with little transparency.”

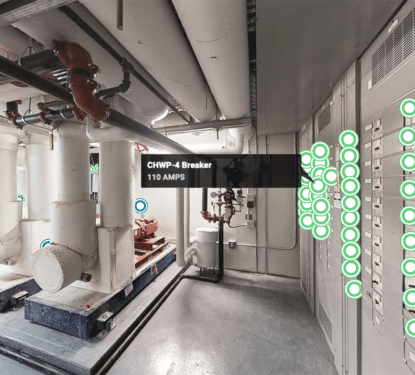

Wieland also points out that there are the various layers of building management – like property and tenant management or facility management, and each have their own requirements and operating systems that are not necessarily designed for integration. Obtaining information on building systems is difficult, therefore, with most data silos where they are neither shared nor in real time. The situation is not helped by the lack of smart technology knowledge among the building occupants themselves, leading to a lack of control over the building’s evolution.

The inevitable and unfortunate result of all this is buildings with high operational costs, excessive energy consumption, low levels of efficiency across the facility, poor workflows and so on. Unless the technology becomes more approachable for building owners and occupants there will continue to be a reluctance to change. Most people naturally fear the unknown, preferring to maintain the status quo rather than choose to learn something new and risk rocking the boat.

If smart buildings are to take hold the offering needs to be simplified so the people who are expected to invest in the technology understand what they’re buying. However, before we can expect that to happen this fragmented industry needs cohesion. If smart buildings are to take hold we must first have a unified view of what a smart building actually is.

“Smart means lots of things to lots of people,” says Wieland. “Smart may mean the building is equipped with building automation or it is IoT enabled. Some say it is smart when IoT data is pushed out in the cloud with some analytics made available. Some use smart apps for space management and, therefore, the building must be smart.”

“What’s not popular is spending a lot on infrastructure because the smart industry has not made a good and verified business case for the potential savings to business. This may explain why energy efficiency projects have a lot of barriers in uptake,” Wieland concludes.